The Moscow Murders: How News Media Fueled the True Crime Boom

The long, strange saga of Brian Kohberger and the four University of Idaho students he was accused of murdering has finally ended, at least for now. Kohberger pled guilty to murder, admitting in court to killing all four people. He will serve life in prison with no possibility of parole, and will thus avoid Idaho’s real life firing squad. This punishment, struck through a plea deal, left the families of the victims divided. For many of us who live in Moscow, Idaho, we are relieved to see this finally end.

I remember all the fear and uncertainty we felt the day of, the day after, and weeks after the news broke with a suspect at large and the police largely mum. In our fear, we were quite desperate to cling to something, anything, that made this make sense and introduced a sense of safety to our lives.

From the moment the public became aware of these murders, the media storm has been massive. National outlets from the AP to CBS to People magazine covered this. News outlets swarmed the local courthouse at every hearing, reporting whatever trickle of news they could. It would be quite a task to track the voluminous number of stories about this, but it seems accurate to call this a “viral mass murder” covered by local, regional and national news outlets.

After public announcement of the murders, news media from all over the nation showed up quickly, maybe that very day, hounding police and city officials with the question “Is Moscow safe?”, an inquiry that makes little sense when you really start to consider it. What is “safety”? How do you identify it? How do you demonstrate it? Is safety no murders? No unsolved murders? No violent crime? No car accidents? While we may answer if an amusement park or car seat meets existing safety standards, there is no such rubric for defining safety in a community.

Incredibly, this was the third mass murder I’ve experienced in Moscow. The first was a mass shooter who killed three people prior to committing suicide. The second was a mentally-ill man who killed his mother and two others, all prominent community members. In addition, there is Wil Hendrick, a gay man who disappeared in 1999, his partial remains found in 2002, and his killer never identified. I don’t think anyone is completely safe from violence, even in the small college town of Moscow, Idaho. However, the repeated hammering of “IS MOSCOW SAFE?” by the news media both increased panic in the town and did not deliver additional information or insights into what had happened.

Next came the seemingly endless stories covering every single development in the case or anything new learned about the victims. No detail was too minor to leave unreported. A Spokane outlet, KXLY, ran over 400 stories related to the murders on their website. This went on for years (Nov 13, 2022 to the publication of this article, August 10, 2025). Any court hearing meant reporters camped outside the courthouse (until the change of venue motion was granted). Students at Moscow High, located across the street from the courthouse, were reminded the day of each court hearing that no one was obligated to speak to reporters.

At one point, 30 news outlets sued to remove a gag order regarding case proceedings (in a bit of hilarity, the petition was denied for not exhausting other steps like filing before lower courts prior to petitioning the Idaho Supreme Court). They argued to have cameras in the courtroom, which they also lost. The petition cited a lofty quote from legal precedent: “Justice cannot survive behind walls of silence. For that reason, a responsible press has always been regarded as the handmaiden of effective judicial administration, especially in the criminal field” (Sheppard v. Maxwell, 384 U.S. 333 (1966)).

What the petition neglects to explain about Sheppard v. Maxwell was that it ultimately vacated a wrongful murder conviction after very heavy and prejudicial media coverage and a “carnival atmosphere” at the trial caused by reporters. The Sheppard case, which may have inspired the Fugitive, was a 1960s true crime sensation, with many newspapers and radio stations asserting the guilt of the accused, repeatedly invoking the victim in emotional terms (“Who speaks for Marilyn?”), and doxxing the jurors mid-trial, resulting in their harassment. In one radio broadcast, “newspaper reporters…asserted that Sheppard conceded his guilt by hiring a prominent criminal lawyer” (Sheppard v. Maxwell).1 I’m not arguing that current media coverage was prejudicial against Kohberger (it seemed quite fair in most cases), but there are certainly parallels between the obsessive coverage of Shepard’s and Kohberger’s criminal trials. It was disingenuous to use a paradigmatic quote from a case that was ultimately a very bad look for crime journalism.

1 Sheppard was found not guilty at his retrial and posthumously exonerated with DNA testing.

2 For my own soul and yours, I will not provide a link to this.

As things wrap up, national and regional news outlets continue to try to wring every last click out of the Moscow Murders. Fox News alleged that this plea deal is a part of a ‘long game’ wherein “left wing activists” pass (presumably lenient) sentencing laws that free him (a very unlikely outcome for any state). Other news outlets trumpet the ultra-dangerous Idaho prison where he is imprisoned, with a mixture of glee and fear (CBS, The Independent, Us Magazine, Vanity Fair). Even now, weeks after his sentencing, new stories continue to roll out each week, none of any particular significance. Most recently, outlets are running crime scene photos, lurid reporting that is hardly in the public interest.2

Moscow, Idaho: True Crime USA

We–the victims, their friends and families, the town and its inhabitants–have become a true crime sensation.There has been a docu-series, dozens of dedicated podcasts and podcast episodes, a book, and undoubtedly, countless blogs.

A search on “Idaho four,” a common shorthand for the victims, on YouTube revealed a disturbing large collection of videos. The results were a mixture of true crime, content from reputable outlets (CBS, Reuters, East Idaho News), other documentaries, and junkets from opportunists (e.g. Megyn Kelly). Much of the true crime media is tiresome, sensationalized and ultimately useless. Did you know that the ladies are sending Kohberger love letters? That he is sentenced to one of the worst prisons ever? That he and Luigi Mangione may have the same neurological disorder?3

3 I realize this focuses on the perpetrator rather than the victims. Out of respect for the victims and their families, I don’t want to repeat online speculation about them, but there is plenty of that in true crime content.

4 I do roll together true crime content producers, their listeners and online sleuths into one Beautiful Katamari ball. These are distinct entities, but they do overlap and in some cases, rely on one another.

It has captured the attention of every would-be online sleuth. The subreddits for “MoscowMurders” has ~148,000 members, while the sub-Reddit for MoscowIdaho has only ~9,700 members. Even the “BryanKohbergerMoscow” subreddit has 12,000 members. Not all were sleuths, some were dedicated to memorializing the victims, which led to discussions about the dangers of parasocial relationships.4

So much of “online sleuthing” looks like online gossip bordering on defamation. Discussions about evidence released, possible motives, possible suspects. An online “psychic” misidentified a University of Idaho professor as the murderer (who had nothing to do with the murders), a distressing event by itself compounded by the millions of views it received. This person was hounded by online mobs that targeted her, her husband and two young children. There is an ongoing defamation suit regarding this that has required significant financial resources. There were many other rumors that implicated innocent people. When local business owners offered their security camera footage to police to fill in gaps in the victims’ whereabouts the night of the murders, one found her family the subject of speculation from online psychics. A cease-and-desist letter fortunately ended that. A Vanity Fair article described the harassment brought on innocent people by internet sleuths and predatory journalists (Fox News was described as a particularly bad offender). In the cruelest twist imaginable, the two survivors of killings, who understandably are deeply traumatized by the murders, were also the target of judgement and false accusations by online mobs. Surviving a mass killing in their own home was not enough; they also had to survive online harassment blaming them for it.

People are going down these rabbit holes, and they’re hyperfocusing on one individual and attacking that individual. You’re attacking, most likely, an innocent person. —Tauna Davis, Idaho State Police (AP News)

The AP asserted that its reporting helped counter the misinformation about the murders.5 However, they only describe that misinformation had spread, and do not provide examples of how their reporting had effectively countered it. In fact, the AP both-sidesed the issue, arguing up that although internet sleuths bring harassment on innocent people, they also find relevant information: “All the rumor and wild conjecture aside, there can be some benefit to crowdsourced investigation”.

5 The AP is reporting on its own actions and thus controlling the narrative of the story and the AP’s role in it.

True Crime: Big Business Interwoven with Journalism

Prior to this case, I had little to no opinion on true crime. It generally wasn’t my shtick, but what did it matter that others loved it? Certainly, it is quite popular, always among top rated podcasts. The genre of “true crime” focuses on murders and has shown a racial preference for white “perfect” victims. Like any genre, it encompasses a wide range of approaches, both salacious and journalistic. Most true crime media tend to sensationalize murders, but one of the first and still very impactful true crime podcast, Serial, questioned the reliability and fairness of the justice system by focusing on a wrongful conviction. And of course, true crime podcasting is big business, raking in millions of views and millions of dollars from advertising revenue and subscriber payments.

True crime relies on actual reporting from journalists: research, interviews, publishing official documents like court filings, broadcasts of court proceedings, and so on. But true crime aficionados are not the only ones with true crime podcasts. Many respected news outlets also run true crime podcasts (New Yorker, LA Times, New York Times). I realized sifting through this content that there is a gradient from ‘journalistic’ true crime podcasts to sensationalized entertainment, without a clear demarcation separating the two. I suppose it’s predictable that news outlets also want a slice of the lucrative true crime pie. That they also want to monetize their reporting, and not just leave it to amateur true crime junkies. The result is a complex web of dependencies between news reporting and true crime content. The simplest explanation is that news reporting drives true crime, and perhaps true crime eventually influences news reporting by building audience appetite for coverage of ultra-violent crime. The reality is likely more complicated, and at this time, poorly understood.

True Crime: An Expression of Copaganda

Attorneys for the media coalition argued that access to information makes it easier for journalists to educate and inform the community about not only the case, but about the judicial system overall.

– KXLY, a member of the media coalition, advocating for removal of the gag order

I struggle to determine what we learned about crime or the criminal justice system from the coverage of this case. What did we learn with regard to how the justice system functions? Or why crimes like these happen? Or what we can do to reduce or prevent violence? How the indigent (i.e. poor) defense system works in Idaho, or how the criminal justice works for most defendants? About jails, bail and pretrial conditions? The answer to these questions is “not much.”

We could have talked about how completely anomalous this case was; most defendants lack the type of robust defense offered to Kohberger. It’s hard to find recent statistics, but a 2000 survey conducted by the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that 66% of state defendants and 82% of Federal defendants used public counsel for the indigent. The right to counsel for criminal charges is spelled out in the 6th amendment of the Constitution, but it’s widely documented how overburdened public defenders are. Idaho, which recently underwent a restructuring of its indigent defense in response to lawsuits alleging inadequate defense, is no exception. And yet, Kohberger received thorough representation by the Idaho public defender’s office, likely because he was facing the death penalty. This could have been a moment to discuss that nearly all criminal cases end in plea deals (98%); that defendants who dare go to trial are penalized for it if they lose despite a trial by jury being a constitutional right. Instead, we got personal-interest articles suggesting that the prosecutor himself favors plea deals for death penalty cases.

In the meantime, what is not being covered or covered inadequately? Bail fraud, for one. When bail agents appear before the Idaho legislature, asking for all sorts of special rules banning charitable bail funds, will this be part of the conversation? What about the guy who sold thousands of diesel cheater devices and installed hundreds into diesel cars? Not a single news outlet covered it; only the DOJ press release provides any evidence to the public that this happened. What were the consequences for air pollution or early deaths due to air pollution? There has been minimal coverage of a lawsuit by an IDOC prison guard regarding abuse of IDOC inmates. What about human trafficking? For all the hand wringing about this, there is very little actual coverage of it, even when it turns out a major agency in Idaho handling this may be engaged in fraud and exploitation, while the whistleblower who reported it was defunded by the state. What is happening to trafficking victims now? Are the services they need available? In some instances there are one or two stories, but that is paltry. When there is ongoing harm, hundreds of victims, risk of future harm and future victims, or poorly understood impacts, why don’t these issues receive more reporting?

The coverage of the Moscow murders has outstripped arguably more impactful acts of violence, such those committed by Vance Luther Boelter, a man who assassinated a sitting Minnesota congresswoman and gravely wounded two others in politically-motivated acts of violence. And there are so many other murders. The AP published a list of mass killings from 2024 alone, most of which I had never even heard of. Meanwhile in St Louis, there are many families of victims of unsolved murders that desperately want answers and don’t want their loved ones forgotten. When there is saturating coverage on one particular murder and very little of others, that reinforces the notion than some lives are more important than others.

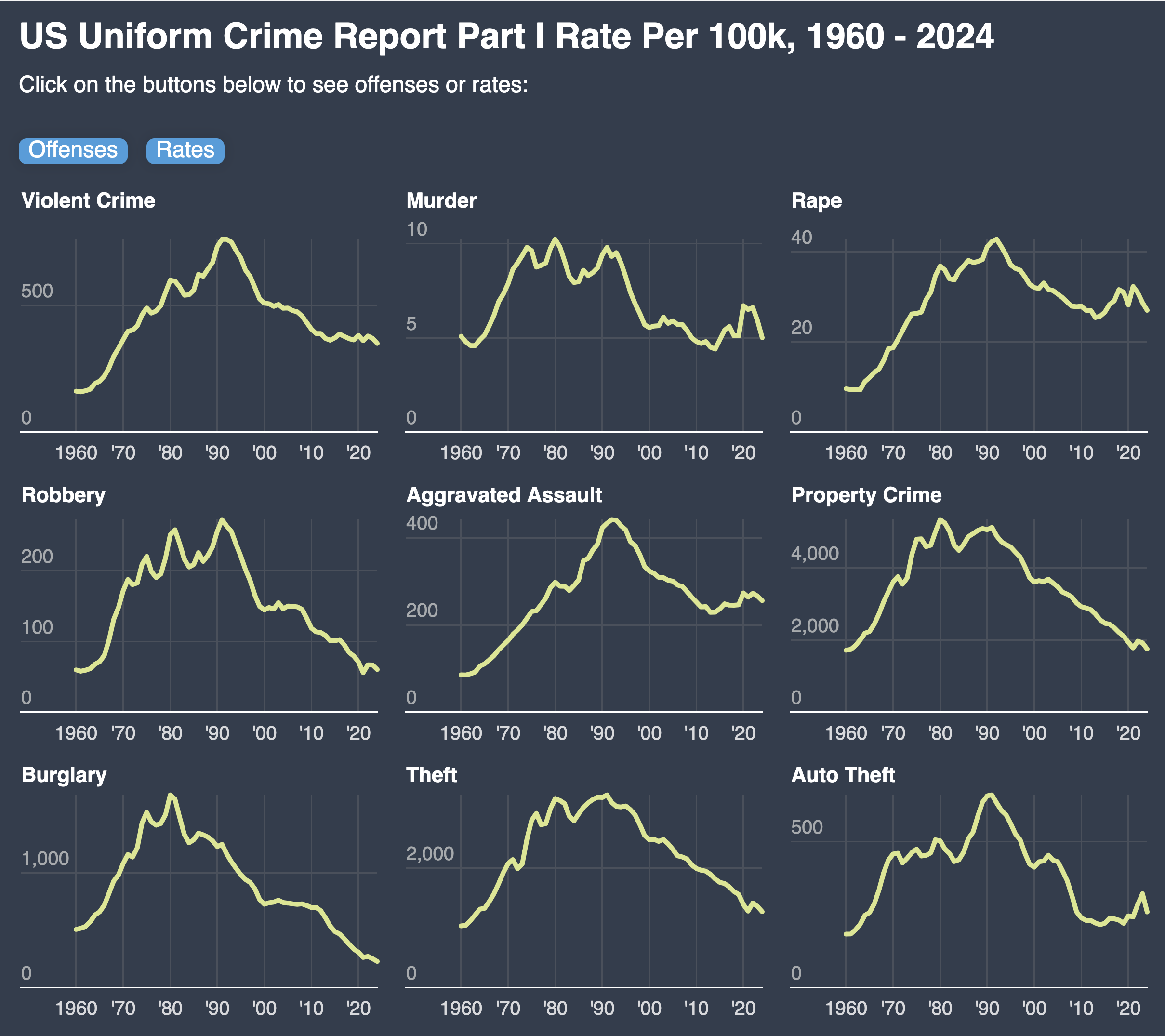

Crimes like this, where a stranger murders multiple people, are very rare; in fact, we are living through one of the safest time periods in the last 3 decades.

And yet the crime coverage is the same as it always has been. Media analysts Josie Duffy-Rise and Hannah Riley call it “anecdotal and sensationalistic”, marked by “round-the-clock coverage of lurid crimes, cherry-picked data, [and] unfounded scapegoating of criminal legal policies.” This matters because media coverage of crime affects our perceptions of safety, understanding of prevalence of crimes, and our relative risk.

A report by Just Journalism, titled “Building a Better Beat:A New Approach to Public Safety Reporting” makes similar points:

…public perceptions of both crime and harm are out of sync with reality. Year after year, people believe that index crime rates6 are increasing, even though they have been declining for most of the last 25 years. And people overestimate the likelihood that they will be the victim of an index crime while underestimating the risks posed by other threats to their health and safety. Simply put, if one of the central goals of journalism is to help people understand the world, contemporary U.S. news coverage of crime is not achieving its objectives. (emphasis added)

6 Index crimes are the eight crimes the FBI uses in its annual crime report, the Uniform Crime Report.

Alec Karakatsanis, in his book Copaganda (2025), describes how crimes beats can distort the public’s understanding of crime and safety in their communities and elsewhere.7 Not only does a heavy focus on violent crimes in news media create the impression these crimes are more common than they actually are, it also shapes public opinion about who or what are threats and how we ought to respond politically to these perceived threats. In his book, Karakatsanis urges us to examine crime news stories critically:

7 “Copaganda” is a term referring to police propaganda. This is P.R. material that supports the priorities and viewpoints of police and is often directly carried over into the news. One example is “officer-involved shooting.” This term was invented by police, saw widespread usage for many years, and is at last falling out of favor among reputable newsrooms.

Why is this story news? Why are other potential stories about things that harm us not in the news?…Who benefits from how the story is framed, from what words are used, from what facts the reporter tells us, and from what the reporter ignores?”

It was through examining these questions that I realized that it was the true crime genre and its creators that benefited the most from the media coverage of Kohberger. In her book Journalism and Crime (2023), former British crime reporter Bethany Usher writes:

Crime is media’s longest sustained genre…With each advancement in media technology, crime journalism has expanded, often, but not always, in response to quests for popularity and profit. Now its capacity to attract clicks, shares, comments and likes makes it a substantial part of digital news agendas.”

Given the intense interest among true crime fandom in the Moscow Murders, this tracks. KXLY indicates that for 2022, articles related to the Idaho murders were the most read stories. An Idaho outlet, KTVB, acknowledges the nation’s “unfettered fascination with true crime” and its national arm runs regular true crime segments.

The Way Forward

Journalism’s crime reporting needs to change if it truly wants to be in the public interest. That doesn’t mean it should not cover murder, or theft, or property crimes, but it should be in balance with how much risk those pose to us.

We should care about anything that harms people. But it is vital to be cognizant of what kinds of harm—by whom, against whom, in which moments, and to what end—are treated as “news.” The news about public safety is a social and political creation that contains judgment calls at every turn, one that creates winners and losers and that could look different if we wanted it to. – Alec Karakatsanis, Copaganda

There are resources for how to do this. Just Journalism has a resources page to help journalists understand how to better cover criminal justice issues. This blog created a short guide for Idaho journalists a few years ago on how to cover criminal justice more fairly.

Something we did learn in this case is that justice is messy and cannot bring “closure” (whatever that is). Some families were relieved by the plea deal, others were deeply angry about it. Surviving roommates are still clearly very traumatized by what happened. The local community is no safer or less safe now than it was 3 years ago; we continue to adapt to that reality. There is no single outcome that can heal people and restore what was lost, but maybe this ending can put people on the path to recovery. At least, that is what I hope.

For me, this case has changed how I feel about true crime. It can be and is often damaging to families, communities and people connected to victims. And rather than educating people, it is a potent force of copaganda, providing a distorted view of crime, harm and the criminal justice system that trickles all the way down to government policies we choose to implement. True crime causes us to fear each other. This is not what any society ever needs, but it is especially harmful now as potent forces work to tear down structures we have built, split communities and generate distrust among us.

We should ask ourselves for any crime coverage: “what kind of public is created by consuming such news?”8

8 Alec Karakatsanis, Copaganda